Martin Bauman hosted me on his podcast Story Untold to talk about the journey that led me to research and write a travel memoir about my Mennonite culture. Have a listen!

Martin Bauman hosted me on his podcast Story Untold to talk about the journey that led me to research and write a travel memoir about my Mennonite culture. Have a listen!

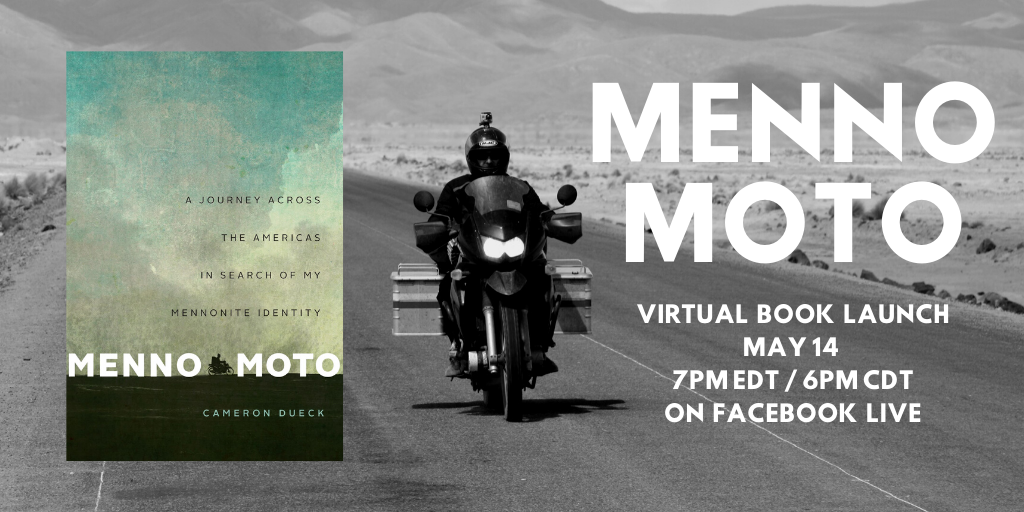

Join Cameron Dueck on Thursday, May 14 for a virtual launch of his new book, Menno Moto: A Journey Across the Americas in Search of My Mennonite Identity. There will be a reading, a Q&A, and the opportunity to win a copy of Menno Moto! Cameron will be joined by his brother, Rod, and writer Dora Dueck (no relation).

Join the event on Facebook Live

https://bit.ly/2SU8XNv

Thursday, May 14, 7pm EDT/6pm CDT

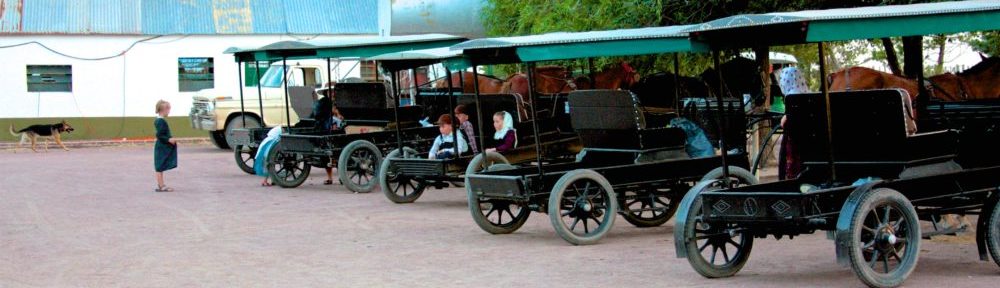

Across Latin America, from the plains of Mexico to the jungles of Paraguay, live a cloistered Germanic people. For nearly a century, they have kept their doors and their minds closed, separating their communities from a secular world they view as sinful.

The story of their search for religious and social independence began generations ago in Europe and led them, in the late 1800s, to Canada, where they enjoyed the freedoms they sought under the protection of a nascent government. Yet in the 1920s, when the country many still consider their motherland began to take shape as a nation and their separatism came under scrutiny, groups of Mennonites left for the promises of Latin America: unbroken land and new guarantees of freedom to create autonomous, ethnically pure colonies. There they live as if time stands still—an isolation with dark consequences.

In this memoir of an eight-month, 45,000 kilometre motorcycle journey across the Americas, Mennonite writer Cameron Dueck searches for common ground within his cultural diaspora. From skirmishes with secular neighbours over water rights in Mexico, to a mass-rape scandal in Bolivia, to the Green Hell of Paraguay and the wheat fields of Argentina, Dueck follows his ancestors south, finding reasons to both love and loathe his culture—and, in the process, finding himself.

To get your copy of Menno Moto, call or visit the McNally Robinson Grant Park bookstore. 10 AM to 6 PM, Monday through Saturday. 204-475-0483.

You may also order online here: mcnallyrobinson.com/9781771963473/cameron-dueck/menno-moto though note that it will take at least a week to process new orders, so for faster service we strongly encourage you to phone or visit the bookstore.

145 years ago today (Aug 1) my nine-year old great grandfather stepped off a paddle wheel ship onto the banks of the Red River in Southern Manitoba. He was among the first of 7,000 Mennonites to come to Manitoba from German-speaking colonies in South Russia, now Ukraine. His landing site was where I chose to begin my motorcycle adventure through the Americas. I crossed 19 countries and rode my bike 45,000 km to find the diaspora that has its roots in that same riverbank, and to discover the Mennonite in me. My book about that search for identity will be released by Biblioasis on March 21, 2020.

I’ve received many messages from people who want to know when they can read the story of my motorcycle trip across the Americas to research the Mennonite diaspora. Those messages encouraged me to keep editing, rewriting and reimagining what has become a very personal project. I’m pleased to finally have some good news to share. I’ve sold the manuscript to Biblioasis, and Menno Moto is slated for publication in Spring 2020.

Biblioasis is an independent bookstore and publishing company based in Windsor, Ontario. It was founded by Dan Wells as a bookstore in 1998, and in the early years it focused on poetry and short story collections. Biblioasis went on to become one of Canada’s most prestigious small press publishing houses and in 2015 they had three books nominated for the Giller Prize. You can read articles about them here and here.

Dan is known for taking a risk on new writers and books that other publishers won’t touch. In that case, I’m proud to have written something the publishing industry considers risky.

Menno Moto documents a culture of fair-haired, blue-eyed people who have created isolated colonies across Latin America. There, they have kept their doors and minds closed for nearly a century, viewing the rest of the world as sinful. These are my people, and they are my story.

In Menno Moto, farmers, teachers, missionaries, drug-mules and rapists force me to reconsider my assumptions about my Mennonite culture, which I find to be more varied than I had dared to hope. I find some of my people in prison for the infamous Bolivian “ghost rapes”, while others are educating the poor in Belize or growing rich in Patagonia. In each of these communities I encounter hospitality and suspicion, backward and progressive attitudes, corruption and idealism. I find the freedom of the road, the hell of loneliness, and am almost killed by accidents and exhaustion as I ride my motorcycle across two continents. I learn that there is more Mennonite in me than I expected, and in some cases wanted, to find. I find reasons to both love and loathe the identity I am searching for.

I hope you’ll buy Menno Moto when it’s published in Spring 2020.

Read this essay as it appeared in the February 22, 2018 The Globe and Mail newspaper.

Dad’s raspy 87-year-old voice was filled with relief that this last bit of business was taken care of. But I also heard uncertainty, a tinge of seller’s regret, over the telephone.

“He’s agreed to the price and it’s a done deal,” Dad said, his voice muffled by half a world of telegraphic cable. “That’s it. That was my last piece of farmland.”

I was in Hong Kong when I received his call, a long way from Canadian land that he himself broke and turned into grain fields. The fields where my siblings and I learned to put in an honest day’s work, the cornerstone of our family farm on the Prairies. The land that had defined him as a Mennonite man, one chapter in our culture’s long history of buying wilderness and turning it into productive farmland. Selling his land meant he was exiting the cut-and-thrust of agri-business. It meant he no longer had a seat at the table when talk turned to crops and taxes, government subsidies and drainage plans.

When Dad bought half the half section, 320 acres we always called Section 10, it’s designation according to the Dominion Land Survey in the 1800s, it was mostly old-growth tamarack and spruce and the ground was covered in luxuriant moss. It was home to bears and bobcats, wolves and wild that would take years conquer. There were no proper roads leading to it, and just beyond it lay mile after thousands of miles of wilderness. It was low-lying peat and prone to flooding. The land was cheap because it was beyond the fringe of civilisation, part of a new agricultural frontier in Manitoba’s Interlake region. The government offered Dad favourable financing terms because he was a young man eager to help build Canada’s agricultural industry, to tame the nation’s vast expanse.

Grainy black and white photos in our family album show him and my mother, fresh faced and smiling as they began carving a farm out of the forest in the early 1950s. They were in their early 20s, poor but filled with the thrill of prospect. It was a grand adventure to them. One picture shows them resting in waist-deep snow while cutting down the pine forest to make room for their first crops, another has Dad on a borrowed bulldozer, pushing brush into long windrows for burning. Then there’s the photo of him standing in his first crop of barley, which grew as high as his chest but couldn’t hide his beaming smile.

“Ahh, those were hard times,” he says when he sees the pictures. “We worked so hard, because we wanted to build something, to have our own farm. That land was everything to us.”

Sold. Sold to someone I’d grown up with, a farmer who will take good care of it, but still, Section 10 is gone. We knew it was coming — he tried for many years to convince my brothers and I to buy it. But none of us wanted this particular piece of land.

Most of my family still lives in Manitoba. I’m the one that has moved farthest away. When we gather near the farm we grew up on, and the heavy Sunday lunch has been consumed, the men pile into pick-up trucks and go for a drive down the rutted dirt roads circling Section 10. It’s always only the men — because land and crops is a man’s game. At least in a Mennonite’s mind it is. We drive and tell stories about picking roots and long hours on the tractor.

“Ohh, do you remember this corner of the field, the roots that we had to pick here?” one of my brothers asks. The truck slows down so we can get a closer look.

“We’d pick them and burn them, and every year the frost pushed up a fresh crop,” another brother adds.

One person driving the tractor, slowly pulling a flat bed trailer. The others walking behind, sinking deep into the soft peat, picking up the remains of the forest and hurling the roots onto the trailer. When the trailer was full we dumped the roots into piles and burned them. Rock picking wasn’t much different — just heavier to lift and harder to dispose of. Hour after hour of hard work, the earthy smell of the land permeating our hands and clothes, the dirt hiding thick in our hair.

“Child labour. That’s what that was.” Everyone laughs.

Dad squirms in his seat. “Ahh, it wasn’t so bad. And there was no other way, if you boys didn’t work hard the farm wouldn’t keep going.”

“We’d clear the fields of roots and rocks, and then it would rain too much and the fields would flood,” one of my brothers continues.

“It was all we had. We had do the best with what we had,” Dad says.

The stories are always about the struggle, the fight against nature. There were no easy gains made on Section 10. And that’s why none of the brothers bought the land. We wanted nothing more to do with land that required such hard labour. The land was important to our family history but owning it would put nostalgia above smart investment, and none of us could afford such costly sentiments.

Yet owning farm land is central to Mennonite identity. It spells security and stability and, most importantly, independence. Menno Simons, the radical 15th-century religious leader for whom the Mennonites are named, never called on his followers to own land. Nowhere is it written that Mennonites must buy and break land. But the faith’s key tenets of isolationism and simple living were translated into practicing agriculture in remote regions, places raw and wild enough that we could do as we pleased. So, for a Mennonite man, land means you don’t owe nothing to nobody. It means you’re your own man.

Mennonites like to tell stories about how we have moved from country to country to escape religious persecution, to find freedom to live the old way. But, truthfully, the moves are often about finding new land. And Mennonites are thrifty. Swampy land that needs draining can be had for cheap, and all it takes is hard work to turn it profitable.

Perhaps we’re influenced by our earliest roots in the Low Countries, where holding water at bay was a matter of survival. In the mid-16th century those skills earned us an invitation to settle, en masse, on the shores of the Baltic Sea. We dug ditches and built dikes, creating an agricultural haven. Then Catharine the Great invited us to move to southern Russia, promising us good land. We accepted, and took a break from our ditch-digging to farm wheat and silk worms on the well-drained steppes.

In 1874 my great-grandfather moved from Russia to Canada in the first wave of Mennonites to colonise the Prairies. He settled in the Red River Valley, where he needed those diking skills again. The Red regularly breaks free of its banks, overfilled with spring melt. In Rosenort, the diked village where both of my parents grew up, the farmers hold their breath every spring, watching the river rise, rejoicing when it doesn’t flood and resigned when it does. We’ve done it in southern Mexico, Belize, all the way down to Paraguay and Bolivia. On a topographical map, many Mennonite settlements are located in deep green territories, where the land dips and water gathers, places the cartographers mark with cross hatchings.

Dad added another chapter to that story when he left the Red River Valley and moved north to the boggy shores of Lake Winnipeg to break virgin peat land. For Dad, digging drainage ditches became as much a part of farming as planting and harvesting, from an annual deepening of ditches already dug with the tractor to hiring heavy machinery to transform the landscape, thumbing his nose at nature. Ditches that led the water off our land and towards Lake Winnipeg. In really bad years the lake flooded, snaking up those same ditches to drown out our barley and canola. Farming the Mennonite way.

No matter how many ditches we dug, the tractors and harvesters still became stuck. My father put rice tires on the harvester — although there was no rice being grown — hoping to better churn his way across his swampy fields. To no avail.

My childhood memories of farming centre around being mired axle-deep in the fragrant peat of Section 10, the tracks filled with seepage. Deep ruts, so deep you had to scramble to climb out of them. I could think of a hundred things I’d rather be doing.

“Why are we farming here? This is the worst place in the world to farm,” I’d say, my hundredth complaint for the day as I grudgingly helped Dad work the land.

“It’s good soil, we just need to drain it better,” Dad said. He slapped at the hordes of mosquitos — ohh, there were mosquitos, big and by the thousands. He crawled through the muck under the harvester to hook a logging chain to the axle. I took the other end of the chain and dragged it towards the idling tractor, hitching the machines together with the clinking steel snake.

“Now start slow. Don’t yank it or the chain will break,” he would instruct.

I crawled into the tractor cab, twisting around in the seat to watch him on the harvester, watching his hand signals. I revved up the big diesel engine until it belched black smoke, eased out the heavy clutch so slowly that my skinny legs quivered with tension. Watching Dad, watching the harvester, the chain, a delicate dance of lumbering beasts. The chain pulled taut and then, instead of the harvester popping out of its hole, the tractor’s spinning wheels dug giant holes in the quagmire, pulling the machine deeper and deeper with every revolution.

I could see my father shouting, urgent, his lips moving but words drowned by the roar of thrashing pistons. He waved his arms for me to stop. I groaned.

“I’ll put another drainage ditch through here and then next year it will be dry,” Dad said as we unhooked the chain and repositioned the tractor on firmer ground. But it was never dry. Some years we had to wait for frost to firm up the water-logged fields before the crops could be taken off. In those years harvest became a race against the snow.

“I’m never gonna be a farmer,” I told him, more than once, as we stood knee deep in bog, working to free the machinery. I said it angrily, with vengeance.

And I stuck to my word. I moved away from the farm and the Mennonite lifestyle that the rest of my family still shared. I lived in Chicago, New York, Singapore, London and Hong Kong, moving further and further away from my Mennonite identity. I certainly didn’t attend a Mennonite church, I rarely found opportunities to speak our quirky Plattdeutsche mother tongue, and digging ditches made for good stories in the bar, but it was no longer a part of my life. I’d scrapped that muck from my shoes for good.

Then, years after I’d left and Dad had long ago accepted that I wasn’t the farmer he’d hoped I’d become, on a trip back to Manitoba to visit my family, I told Dad I had some money I wanted to invest. His eyes lit up and he leaned forward in his chair.

“Hey, there’s some land for sale near here,” he told me. “It may not go up in value as fast as those stock markets do, but it will always be there. They’re not making more land.”

The language of land — drainage, fences, good soil, stoney or not — was one I’d never learned to speak. But the idea of owning land, my very own land, still appealed to me. It appealed to the Mennonite in me. I’d thought the Mennonite in me had faded, replaced by urbane tastes and international lifestyle, so I was surprised at how his suggestion struck a chord in me. Drifting through the world’s capitals earning a living with my pen was good fun, but owning land, now that was permanence. That was long term planning, building something for the future. The advertised plot was a few miles from our family farm. It was cleared of trees, already tamed and well drained. No digging of ditches needed. It promised an easy, painless path to becoming a respectable Mennonite man.

So I bought the land with a loan from the home town credit union, a small place, where my family had banked for so long the manager still recognised my voice on the telephone. It was with great satisfaction that I took the “For Sale” sign off the gate and walked into the field for the first time.

I kicked a clod and thought, “That’s mine.” I eyed the slope towards the lake, pretending, for a moment, that I knew something about land. I had friends and family that owned thousands of acres so there was a tinge of city-boy sheepishness to my pride in owning this modest plot. I knew I was reaching back to something that wasn’t me anymore, that I had skipped some important steps. I hadn’t broken my own land, planted it with crops, let the land tether me to a place, a community, church and family that consumed me all day every day for my entire life. It wasn’t the same as what Section 10 had done for Dad. This land had not been watered by sweat from my father’s brow. It did not come with stories of hardship, work and progress. And I’d never be a real farmer like my Dad. But I did have a piece of my own land.

Solid, well drained land, and it’s not for sale.

I’m at the airport in Santiago, Chile, about to fly to Winnipeg. Bike is sold, gear either tossed, given away, or jammed into my bags. I’m done and heading home! I set off for home with a rather empty bank account (budget? Oh, that! It’s busted, in a ditch somewhere in Colombia!) but I feel like the richest man alive with all I’ve seen and learned. Once again, I’ve been changed by a challenge, a journey, a goal achieved. I am incredibly lucky to be living the life I dreamt of as a child, and even luckier that you want to read about it.

Thank you for reading this blog over the past seven months. It’s been a pretty special journey. Not only have I see a good chunk of the world (19 countries!), but I have learned so much about my heritage and who we are as Mennonites. Now to fit that into a book!

Thank you to all those I’ve met along the way. The long-lost cousins, the Mennonites in far flung corners of the Americas, the bikers, the new friends made on ferries, dusty roads, in dodgy hostels, in splendid campgrounds. You, more than anything, made this journey worth the effort.

Many people have sent me notes in the past months. Encouragement, contacts, questions, challenges and advice. I’m sorry if I have not responded, but they were all deeply appreciated. Thank you!

Next up, seeing my first film, The New Northwest Passage, up on the silver screen at the Winnipeg Real to Reel Film Festival. It plays on Feb 16 and 17, I hope to see some of you there. Then, it’s back home to Hong Kong, where the real work begins…

Keep checking in for updates on the book, film, and my next adventure.

Slow down for curves,

pullover to help those in need.

But never stop,

because there’s even greater things ahead.

Cameron

Die Mennonitische Post, arguably the widest read and most influential Mennonite newspaper in the America’s, did a short story about my trip. You can download the pdf file here. FYI, it’s in German.

I entered Brazil three days ago, though it feels like a week. This is the 16th country I’ve been in on this journey. The change from Paraguay was immediate and huge. Brazil is clean, pretty, green, civilized and wealthy. I like it, lots, although I am back to square one in terms of understanding what people are saying. Learning a bit of Spanish hasn’t done me a lick of good in understanding Portuguese.

I had my first major accident of the trip shortly after entering Brazil. A truck was stopped on the highway. A car in front of me blocked it from my view. The car swerved to avoid the truck at the last moment, leaving me with only meters of braking space. I was doing about 100km/hr and had only a split second to lock my brakes, so I estimate I was doing 70 km/hr on impact. My last thought was “This is gonna be a big crash”. But I got up immediately after everything stopped moving, and thought “Hmm, that wasn’t so bad.” I have not yet figured out the physics of it. The truck was pushed forward by the impact. This picture doesn’t show it well, but the truck bumper was torn clear off the frame. There was significant breakage/bending of the metal/frame. My bike suffered only some broke plastic on the fender and faring. The forks/wheel/handlebars are straight and true. I can’t figure out what absorbed all the force, and a witness on the scene was as puzzled as I was, as were the cops, EMS people, the driver of the truck, etc. I woke up VERY sore the next day, and I still am feeling like I was beaten with a lead pipe. But nothing was broken. Yes, I’m a lucky man. I have no collision insurance, so I had to pay the guy about $180. I could have just driven away (even the cop told me that) but that didn’t feel right, as technically it was my fault (although he was an idiot for parking on the highway like that). Life goes on.

A few bikers pulled up and helped me get my bike back on the road and negotiate the payment, etc. Thank you Volnei and Marcel!

I spent my first night in Brazil camped in a soya bean field. I look rather proud of myself.

The next morning I rode into Curitiba, Brazil. As I entered the city I passed a Kawi shop, so I stopped to say hello. They offered to give my bike a proper wash, and then they escorted me to a cheap, clean and cheerful hotel in the center of the city. Thank you Rhino Motorcycles.

Curitiba and the surrounding area is home to about 8,000 Mennonites, most of whom came from Russia/Ukraine/Siberia in the 1930s. This is Maria Duck (nee Kroeker), who fled Siberia at 5 years old, crossing the Amur River into Northern China and living in Harbin for about 1.5 years before finding her way to Brazil.

Witmarsum (named after Menno Simon’s birthplace) is the biggest colony. A lovely little village filled with intelligent, educated and open-minded Mennonites who have embraced Brazil as their home, at least the ones I met. Mennonites have a long and rocky history of resisting change, but in this case here I sensed a good balance of pragmatic acceptance of the onward march of time and continued pride in their Mennonite history.

Lena Harder is 83, and fled Siberia when she was 1 year old. She worked in the Witmarsum hospital for years, and now runs the museum that is housed in the same building. I asked her what she thought would become of Mennonite culture in her area. “Few kids these days can still speak Low German, they all speak Portuguese. But it will continue to exist here for a few more generations, I’m sure of that. It’s just part of life, we live in Brazil and we have to change and adapt to the culture around us,” she said.

I spent more than a week in Loma Plata, Paraguay. This colony was created by Mennonites who left Canada in the 1920s when the Canadian government said they had to start teaching their children English in school. They had a brutal first few years carving farms out of the “Green Hell” of the Chaco. Today it is a fairly open, forward thinking colony (with Spanish as the main language in school), though many of the stereotypes still hold true. They are still struggling to come to grips with being a part of Paraguay, rather than just having a mini-state within the country. It’s the biggest colony in Paraguay, and they have become very rich through farming and industry. They are descendants of families that came to Canada from Russia on the same ship my great Grandfather came on in 1874.

It was election time when I was there, and Andreas Neufeld is the outgoing president of the co-op, which runs just about every big business in town. It has annual revenues of $750 million. He has some interesting views on what Mennonites need to do to survive, many of which included more cooperation with the national government and better integration with Paraguayans. I agree.

These two dudes at Classic Moto helped me fix my leaking “chjiela” (radiator), put on a new tire and make other small repairs to the bike. Thank you Randy Fehr and Dorien Funk for the laughs, mechanical help and gallons of tereré you served me across this counter.

The old Explorers Club flag and I in front of the first Mennonite church in LatAm, in Loma Plata, Paraguay. I told the club the mission of this “flag expedition” was to get a sense of what modern Mennonite culture is. I think I’ve got a pretty good idea by now.

Helmut Neufeld and David Fehr spent a day showing me Menno Colony and a few historical spots in the area.

The next day I drove to Porto Casado with Rudy Harder (above), David Fehr and his brother Peter. This is where the Mennonites first arrived in the Chaco. We visited the cemetery, where the men found some of their relatives that didn’t survive the trip.

We ended the day by fishing in a Chaco pond. It was a lovely afternoon of fishing, eating, and telling stories. This is David Fehr.

Peter untangling his line…

This is just after Rudy put his trousers back on. He lost his line in the pond, so he had to strip down to his undies to retrieve it. I didn’t take any photos, but we gave him a pretty hard time for it. I think they had blue polka-dots on them.

A cookout over the fire, where David whipped up a giso (below). I’m told it’s an institution among Chaco ranchers, and I ate it several times while I was there. Very tasty.

The first time I entered Brazil, in 2004, I did so illegally without a visa. I was caught and sent packing. I did it again on this trip, sneaking across the bridge from Paraguay to go see Iguazu Falls and then crossing properly the next day, since I only have a single-entry visa. And when I got to the falls…a rainbow!

Yesterday I spent the day with brothers Herbert and Werner Bartel as they inspected part of their 8,000 hectare (20,000 acre) estancia in the middle of the Paraguayan Chaco.

Herbert and Werner (L-R). They live in Loma Plata.

Herbert Bartel

One of the ranch hands. He grew up with Werner and Herbert and spoke Low German fluently.

This cowboy appears to be getting conflicting instructions from the two brothers.

The US can no longer lay claim to “cowboy culture”. I’ve seen a countless horses and full-time cowboys in Central/South America, a lot more than you see driving through North America.

The cattle are a mix of Hereford (calm, gain weight fast) and Brahman (hardy, can handle the heat). The breeding is still a bit hit and miss, some of them appear to be almost pure Hereford or Brahman.

Werner is also a dentist and runs a clinic together with his son.