Finland is opening some of its secluded military islands to the public, creating a string of new cruising destinations and adding to the many gems of unpolished history spread across this remote archipelago.

This story was first published in the February 2018 issue of Cruising Helmsman.

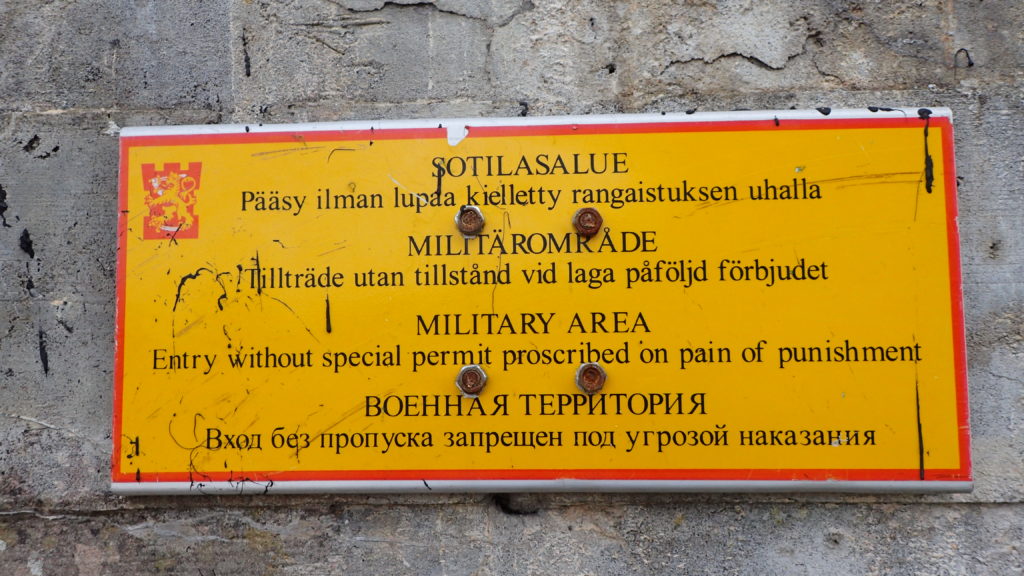

The waters approaching Örö are treacherous. Submerged rocks abound, and if you don’t pay attention to your charts you’ll end up swimming in the cold Baltic Sea. It only makes sense, as the inhabitants of this Finnish island have spent the last century with guns in hand, trying to keep visitors at bay.

We handed our sails and motor into the marina under the gun-slit gaze of a weathered concrete bunker, knowing the gun barrels were plugged with concrete while the bunkers are now a tourist attraction.

Örö served as a grazing pasture for local farmers until the early 1900s. Then, as the First World War loomed, Tsarist Russia built a fortress on the island to keep ships away from it’s nearby capital, St Petersburg. Civilians were prohibited from visiting the island and the Russians embarked on a base-building frenzy, from artillery batteries, observation towers, barracks, jetties and cobble-stone roads to warrens of trenches.

When Finland declared independent in 1917 Örö was handed to the Finnish Defence Forces — and remained closed to the public. It was an important defence base during World War Two, and it remained an active base until 2004. Only in 2015 were Örö and all of its buildings transferred to the park system and opened to the public. Örö is only about a 25 mile sail southwest of the region’s major yachting base of Hankow.

The second ö in Örö means island in Swedish, the language of choice for many locals — which points to wars that took place even before this island was militarised. Many of the decommissioned islands have been occupied by Swedish, Russian and Finnish soldiers over the centuries, so each layer of peeling camouflage paint has a story to tell.

On Örö,, the rusting weaponry still gives off a Cold War chill. The historical preservation has been careful and unobtrusive, allowing each new visitor to feel as if they’ve stumbled upon a secret.

If your charts are a year or two out of date, like mine were, the secret can suddenly become pressingly more realistic.

“There’s a north cardinal up ahead,” my girlfriend told me as she helmed our borrowed H323 through the skerries south of Örö. We were on a three-week cruise, with this being her first ever sailing trip. I was navigating, my nose in a book of charts.

“What? You must be seeing something else. There’s nothing on the charts,” I replied, scanning paper and screen simultaneously.

The lack of marks on my charts explained why we were sticking to a wider channel, tacking well clear of the shore and watching the depth meter with a nervous eye. Finland’s waters are notoriously rocky, but the main cruising areas are well marked, with excellently maintained and positioned cardinals, transit marks, lighthouses and cairns. It’s like sailing in a navigational classroom.

“And there’s an east cardinal…I think I can see another north over there.”

These marks for small craft had been laid, or maybe only revealed, in the past year or two, if the date on my charts were correct. I had no doubt the Finnish Defence Forces had these waters well-charted, but still, it felt like we were in remote waters.

Once we were safely moored on Örö we wandered the many hiking trails that wind through forests and over windswept rocky shores. Sprinkled across the island are barracks and mess halls painted the rusty red colour favoured by Scandinavian cottage owners. Örö felt like a summer camp, until we stumbled upon guns with barrels big enough to support a bridge. A radar whirred and spun atop a communications tower, reminding us of Örö’s less peaceful past. Each headland and windswept hill is honeycombed with bunkers and gun positions.

That night we sat, naked and sweating, in the marina’s new sauna, a Scandinavian chic and minimalistic building nestled among the birch trees. An expansive veranda led to a pier, from which steaming pink bodies were being launched into the frigid sea. A full moon bathed the rocky shore in light and turned the leaves of the forest silver. War seemed far away.

Some of the decommissioned islands are just outside Helsinki’s main harbour. Vallisaari was known for centuries as a place where sailors could take fresh water. When Sweden and Russia were at war in 1808 the Russians used Vallisaari as a base, and the island was only opened as tourism destination in 2016. The nearby islands of Isosaari and Lonna, all part of the Helsinki Archipelago, have similar stories to tell. Limited access has allowed threatened wildlife species and habitats to thrive on these islands, making them popular with scientists and eco-tourists alike.

While the bucolic natural settings have made it easy to turn the islands into parks, some decommissioned islands can’t shake their rough character quite so easily. On Utö, 25 miles to the southwest of Örö, the cruising boats are outnumbered by beefy coast guard ships and working boats that have to earn their keep. Utö has had a weather station since 1881 and is the southernmost year-round inhabited island in Finland, but the island feels like a place you are sent to and where you remain out of a sense of duty. Here the bunkers carved into granite feel colder, harder, more dangerous. In reality, Utö has also been a place of refuge. The island and its sailors formed the backbone of the rescue effort when the MS Estonia ferry sank nearby in 1994.

There was a cold, stiff breeze hitting Utö from the northeast when we were there, and it made me wonder about the island’s welcome. But then it came time for one of the handful of sailing boats to leave the dock, and the warm heart of these waters showed. Helping hands began to emerge from cockpits as the departing sail boat started her engine. Warps were run ashore, instructions shouted into the wind, and the boat began to back out while the sailors ashore controlled her head and made sure she got away cleanly. Here, boats moor bow to the dock, with a hook on a stern line to catch the mooring buoy. Boats run their anchor from the stern in smaller marinas without buoys. Most local boats have a strap line on a spool at the stern to make mooring easier.

A spool of strong line on the stern also makes it easier to adapt to local customs in natural harbours. In the Finnish archipelago the land falls into the sea so steeply that in many places you can moor your boat directly to the rocks — a frightening exercise for uninitiated sailors. The anchor is dropped off the stern, and bow lines are tied to trees or pitons pounded into cracks in the rock. Then you jump ashore off the bow and explore your island.

Even in the high season of June and July you can have a cozy bay all to yourself. The forests are wild and pristine, filled with wild berries — within a one-week span we picked blueberries, strawberries, raspberries and cranberries — as well as wild mushrooms, if you dare. While there are summer houses sprinkled across the archipelago, the land use customs dictate that as long as you’re not moored right in front of the property and give everyone a bit of space and privacy, you’re allowed to go ashore anywhere you want.

When you run out of beer and locally smoked fish, there are scores of small, affordable with basic services and friendly advice. The islands have three main mooring options: Natural harbours, whether anchored or moored to the shore; basic marinas, with a toilet and picnic table near the dock and not much more, are free; service marinas, which range from small family-run affairs that offer basic amenities to professionally-run marinas with fuel and repair support. Service marinas charges anywhere from 15 to 40 euros for a 40-foot boat, depending on their location and services.

Foreign boats are rare, and locals are surprised to encounter sailors from Hong Kong in their homely little ports. We borrowed Valaska from a friend, and she flies the Finnish flag, so in every port there was an awkward explanation — we’re not Finnish, we don’t speak Finnish or Swedish, we’re not from around here, but hello all the same. We saw a handful of Germans, the odd British, Estonian or Russian flag, but the vast majority of the boats were from Sweden or Finland. It only added to the feeling that we were discovering something special.

But the discoveries are not limited to old guns and underground bunkers. A dusty patina of history also covers many of the civilian islands that have transitioned from industry and other functions to nature tourism. Most of them are within an easy day’s sail of each other.

Själö was once home to a mental hospital and leper colony — today it’s a marine research center and quiet marina. Nearby is Jussarö’s abandoned iron ore mine, which became a military training ground before even the soldiers went home. The island, now a nature reserve, advertises itself as Finland’s only ghost town.

Helsingholmen is also on that list. When I told a fellow sailor that I preferred rustic, quiet marinas to the full-service ones, he showed me the island on a map.

“There’s just one family living there, running the place, selling some fish and keeping the island alive,” he said.

We arrived in Helsingholmen after a long day of dodging squalls and running in front of a 25-knot breeze. It was nearly dead calm in the bay. Children were playing on the lawn and the smell of smoke and fish drifted through the air.

Helsingholmen has been inhabited by farmers and fishermen since the 1770s, but now it’s just the Andersson family left. I went ashore to pay our marina fee and instead of a cash register found a wooden box nailed to the wall of an old barn, on the honour system. Smoked fish and bread rolls that were still warm from the Andersson family oven were on offer.

A hike across the island took me past abandoned log cabins with leaky roofs, 18th century farm machinery that was slowly becoming part of nature, and overgrown pastures carved out of the forest. The whole island felt like a museum piece.

The sun was beginning to set — which happens late, if at all, during the Finnish summer. I found a rocky outcrop that faced mainland Finland. The sea chopped at the rocky shore, trying to tear out the reeds that grew in the shallows. My sailing voyage through Finland’s archipelago was coming to an end, and I looked out across the water we would cross the next day. We would sail east, towards the bustling port of Hankow and beyond that the capital, Helsinki, and back into the present.

Follow

Follow